Iteration 2 - From Scientific Discovery Games to Citizen Participation in Urban Planning

Iteration 2 spans a timeframe of two weeks, between 12 September 2020 to 25 September 2020.

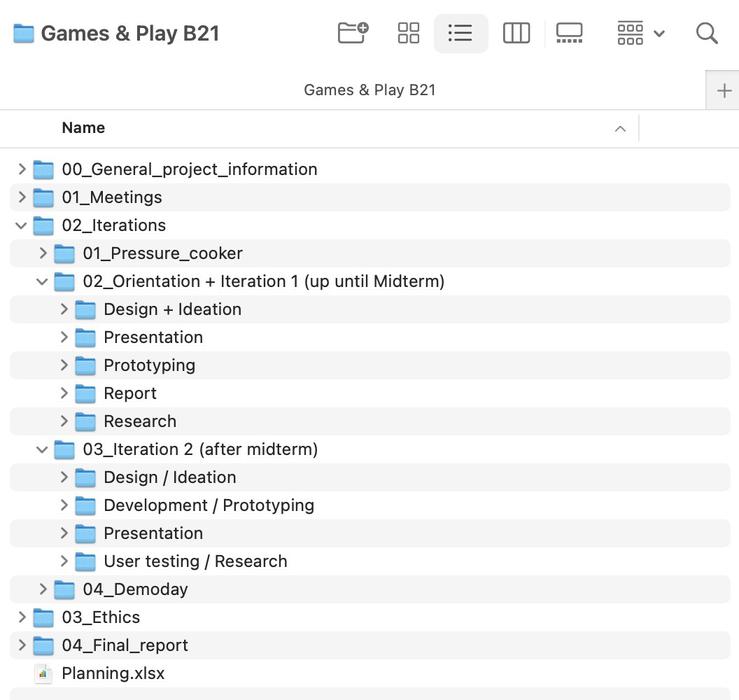

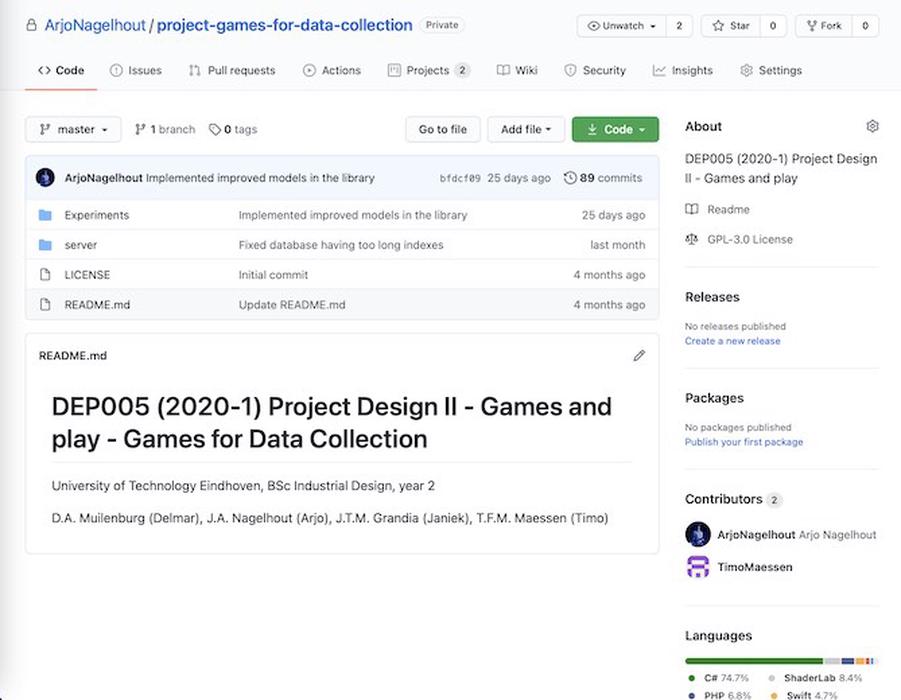

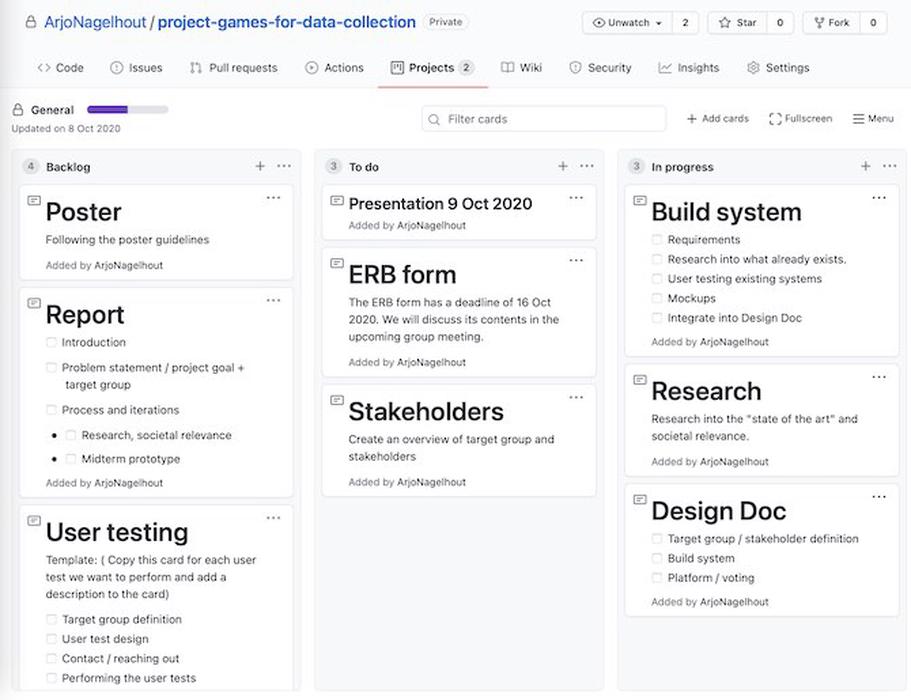

Adding structure to our process

We started setting up the project in a professional manner, creating a well structured shared Google Drive folder, as well as a Github repository with Kanban-style task management and a global planning. We also set up meeting agendas and started writing minutes. This was useful because it would allow us to meet effectively and make consistent progress, especially with the reliance on online collaboration.

Google Drive folder structure

GitHub repository

Kanban-style task management

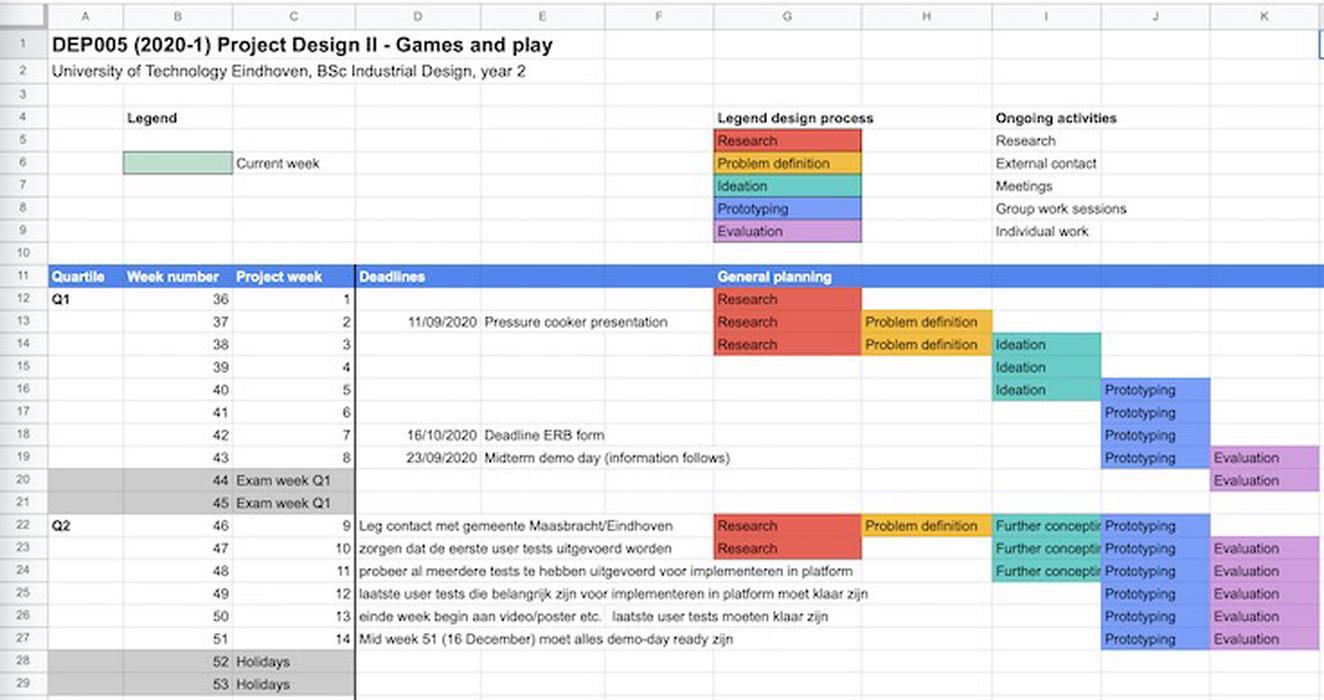

Global planning of the entire project

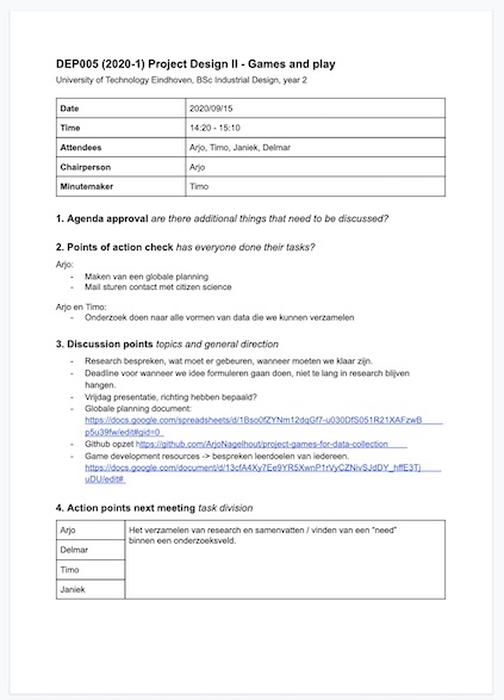

Filled in agenda template for a meeting

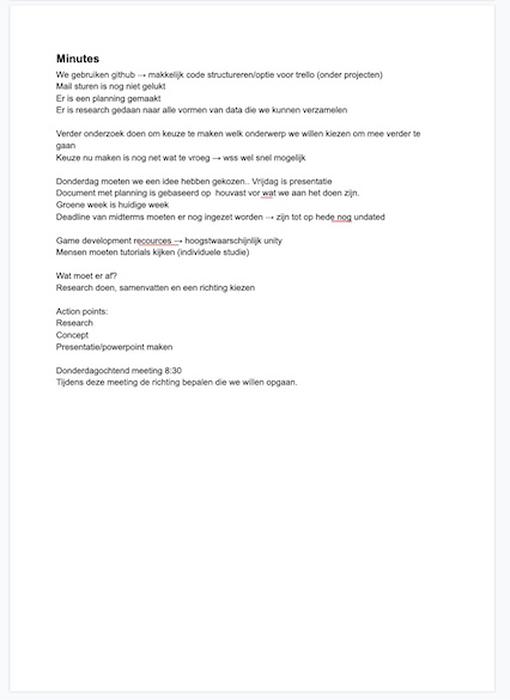

Minutes for a meeting

Diving deep into the world of Citizen Science Games

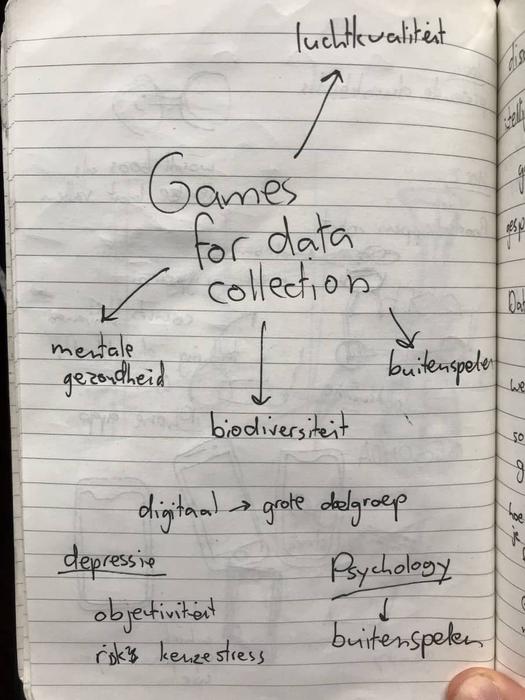

After our first concept pitch in the pressure cooker, we first wanted to gain further understanding of the scientific world and look into all possible directions we could go in. This, because we immediately jumped into biodiversity, but without looking at other opportunities first. As design students with rather limited experience with the scientific world, we dove deep into the workings of journals, conferences, papers and research in general. Next to that we mapped all scientific disciplines to get an understanding of the breadth of scientific research (See the following video).

Our rather long document on citizen science games and the scientific world

Aside from gaining understanding in all scientific disciplines, we looked further into games that have already been made in this field, also known as the earlier mentioned scientific discovery games or citizen science games. Examples of these games are games such as Foldit, where humans’ spatial awareness is used to solve protein folding problems, or Galaxy Zoo, where people help classify galaxies. We quickly came to the conclusion that we wouldn’t be able to conduct meaningful research on our own in many disciplines, because we did not have the expertise to know what we could improve on with existing research.

That is why we aimed to reach out to researchers to see whether we would be able to work together on research. That would allow us to focus on designing the game and the potential researchers to give us guidelines for what kind of data they wanted to get out of the game. This approach was also taken by Foldit, which was the result of a tight collaboration with expert scientists in the field and the designers and developers (from “The challenge of designing scientific discovery games”, 2010).

We reached out to Claire Baert, the founder and maintainer of citizensciencegames.com and were planning on reaching out to many more people, but getting a reaction back took a long time. That is why we continued our project without contact with researchers or experts in the field.

The shift to citizen participation in urban planning

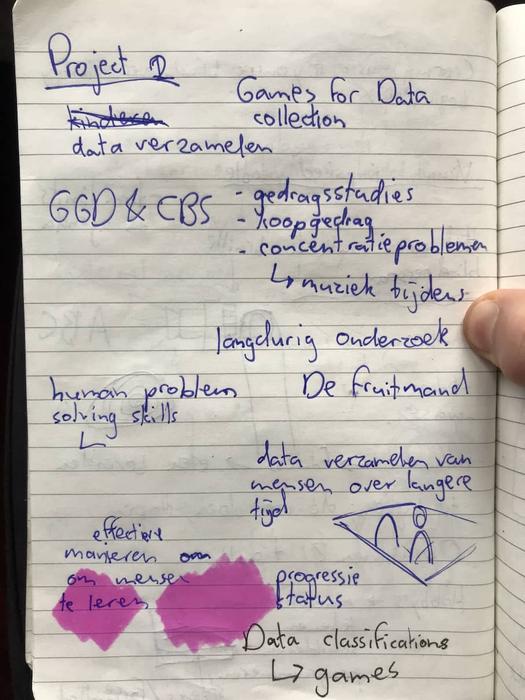

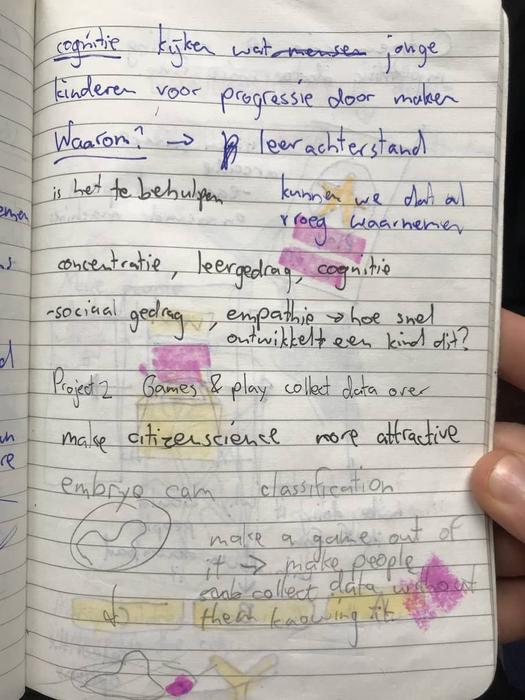

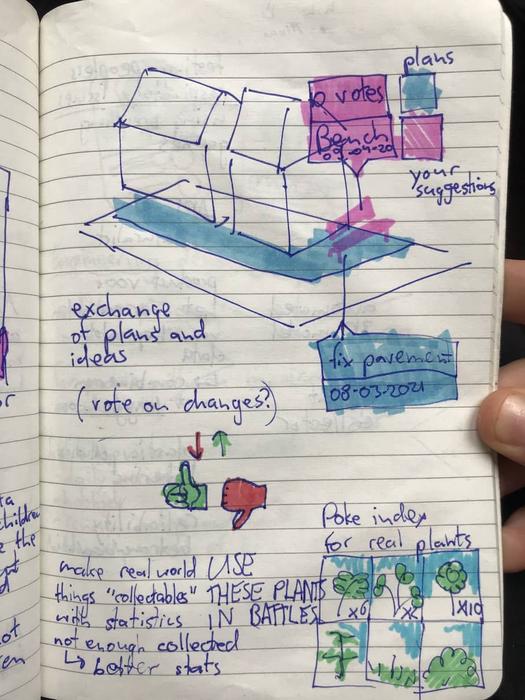

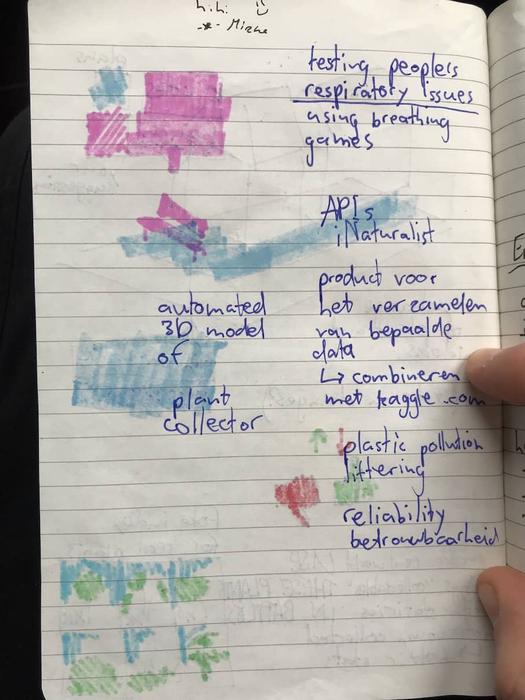

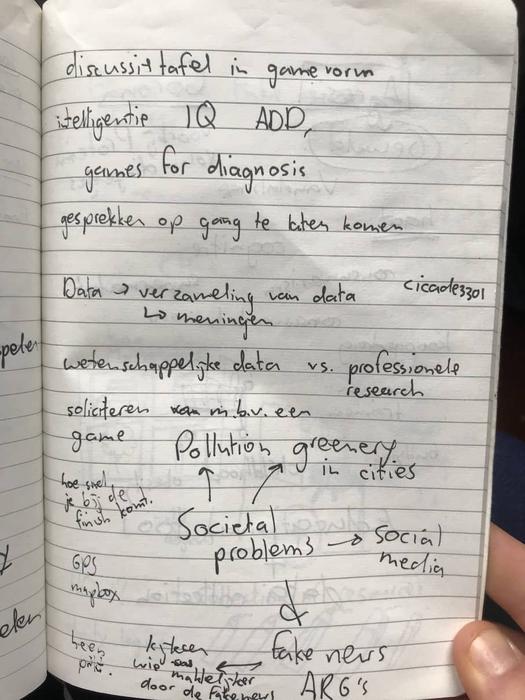

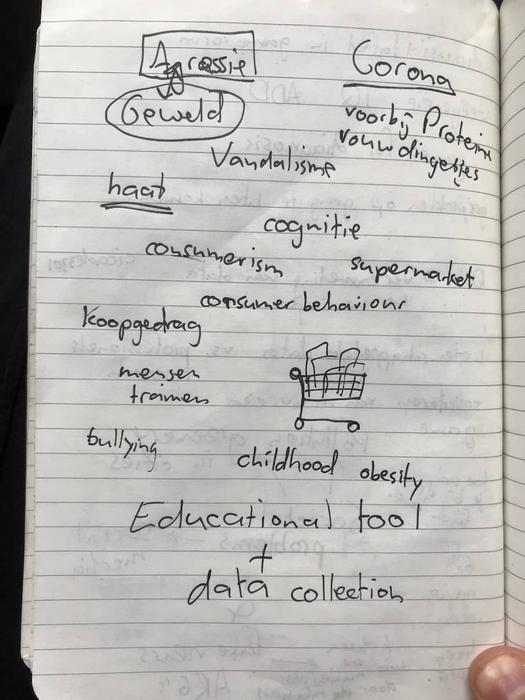

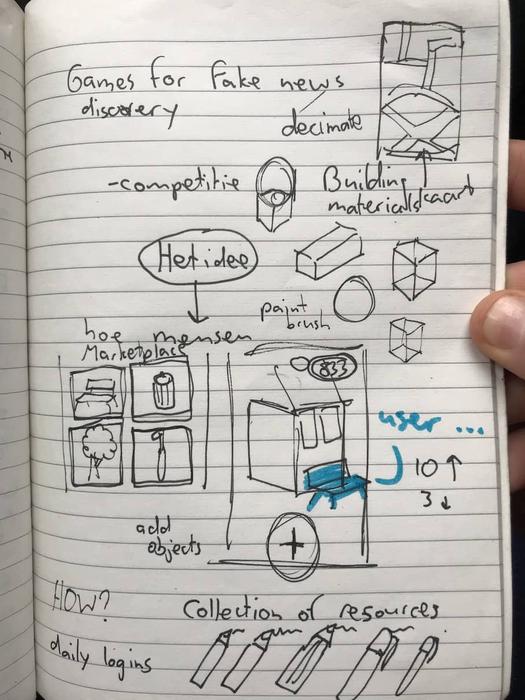

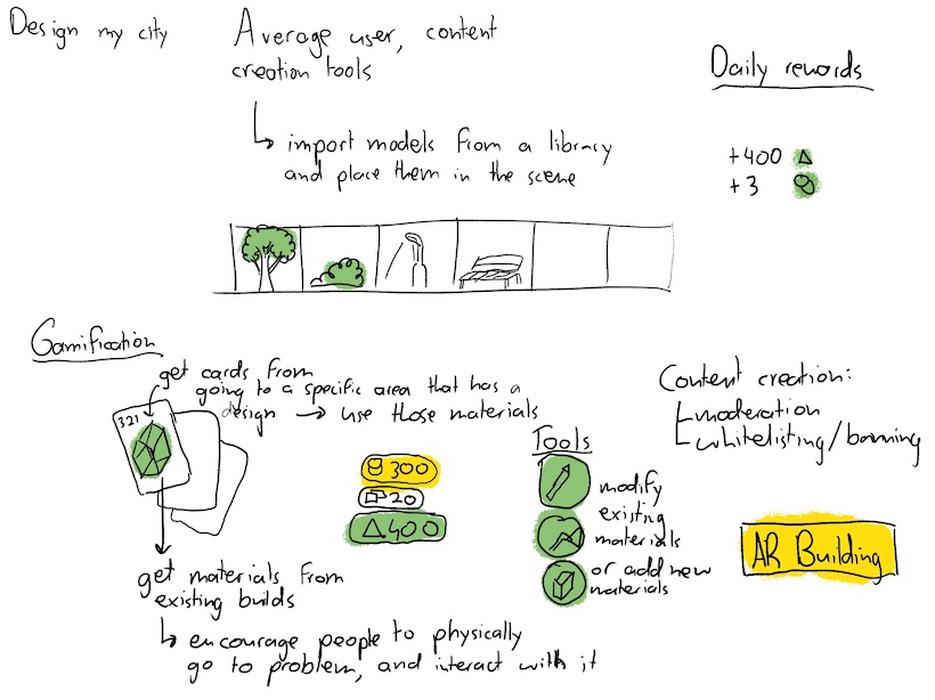

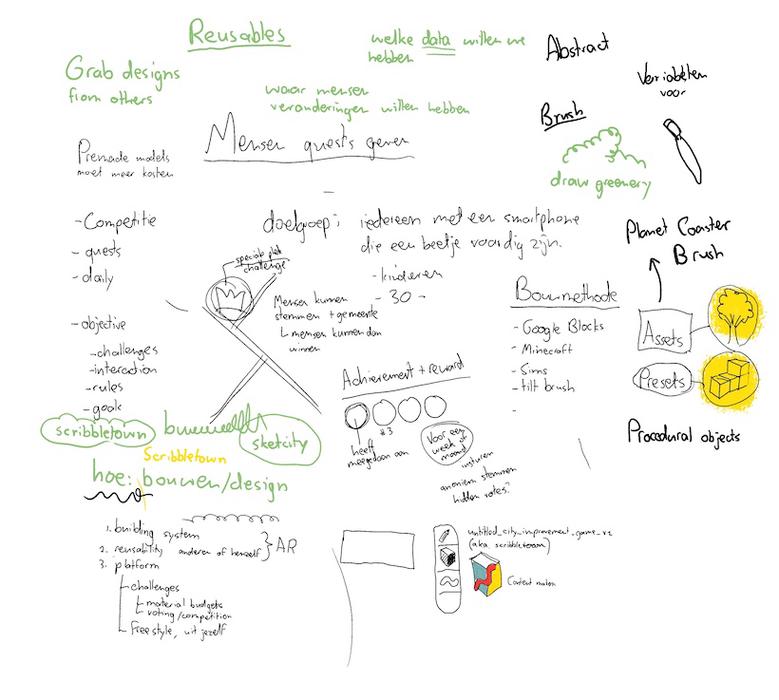

We continued looking into the many possibilities, from behavioural science and cognitive psychology to collecting a variety of data on the urban environment. We even went back to the original idea of an improved and more attractive version of QuestaGame for indexing biodiversity. But then a crucial pivot point occurred during our meeting at the 22nd of september. An idea of collecting data on what citizens want to improve in their neighbourhood (Notebook page 5 and 6), which was initially rejected because of its non-scientific application, was brought back to life and we started looking into it (Notebook page 11). We interpreted the project description for Games for Data Collection in a broader way, and this gave more breathing room for what kind of data we wanted to collect. We weren’t limited anymore to creating the range of scientific discovery games we found in our research.

Notebook page 1

Notebook page 2

Notebook page 3

Notebook page 4

Notebook page 5

Notebook page 6

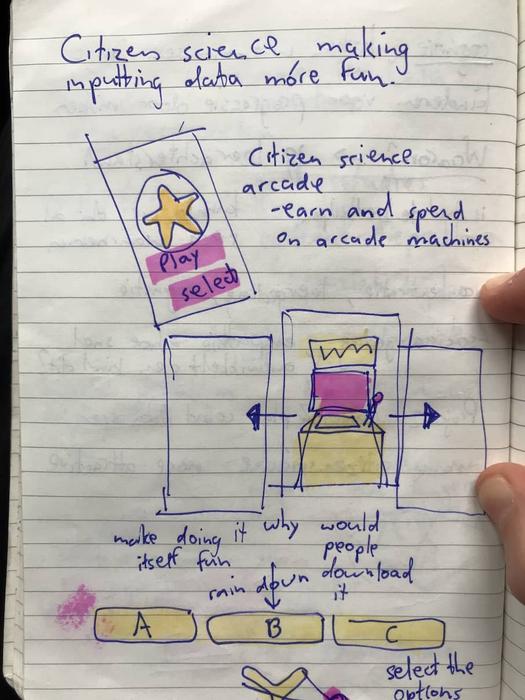

Notebook page 7

Notebook page 8

Notebook page 9

Notebook page 10

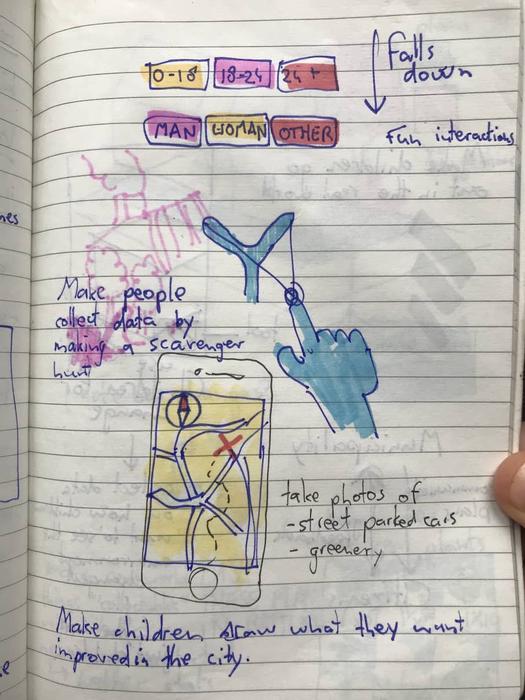

Notebook page 11

Notebook page 12

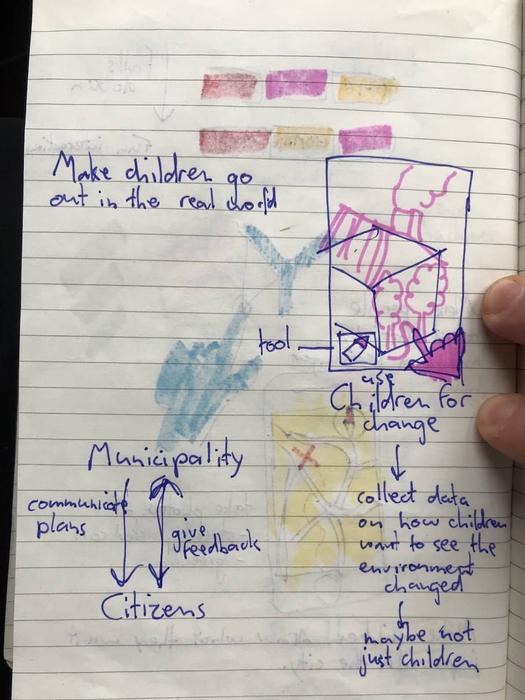

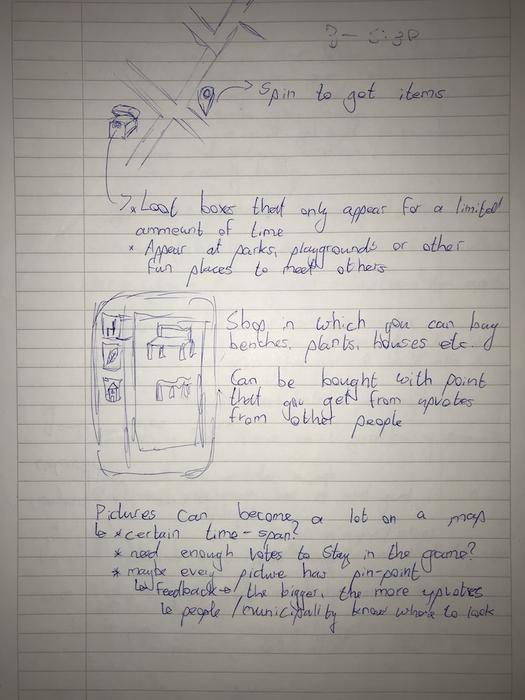

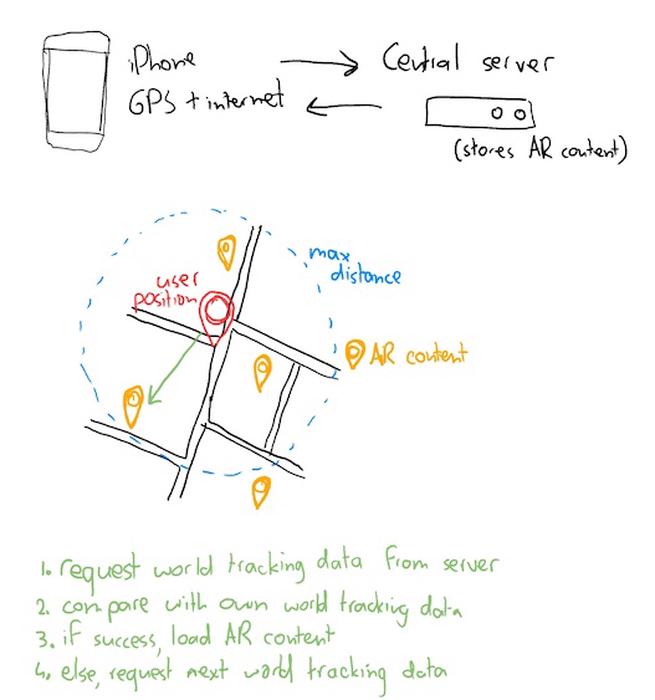

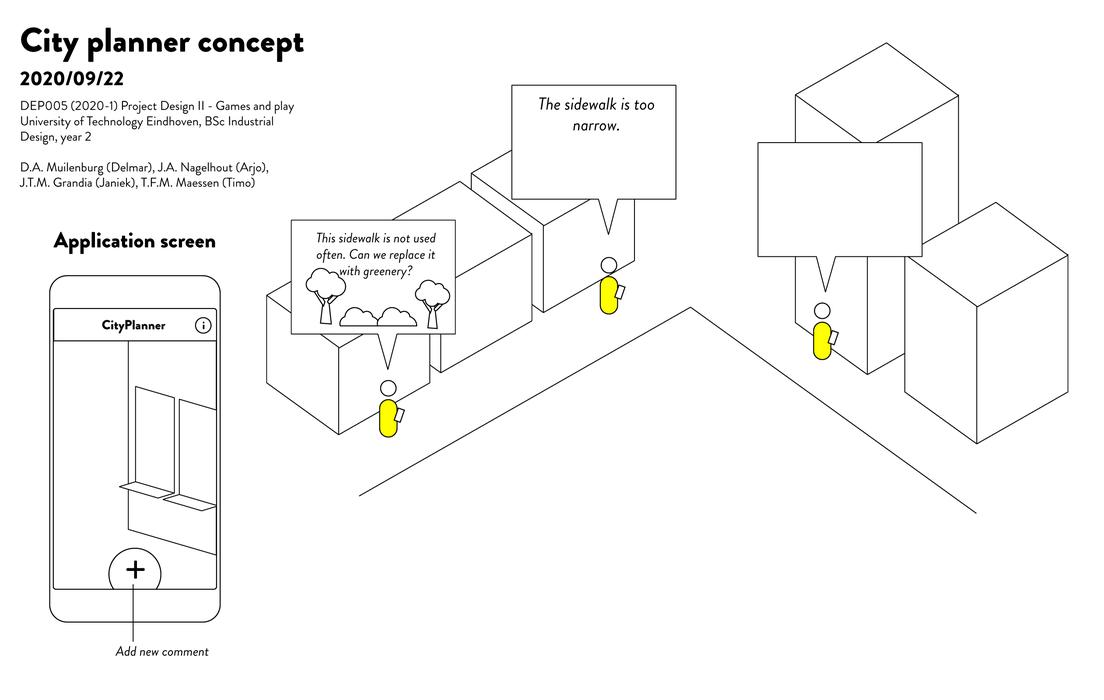

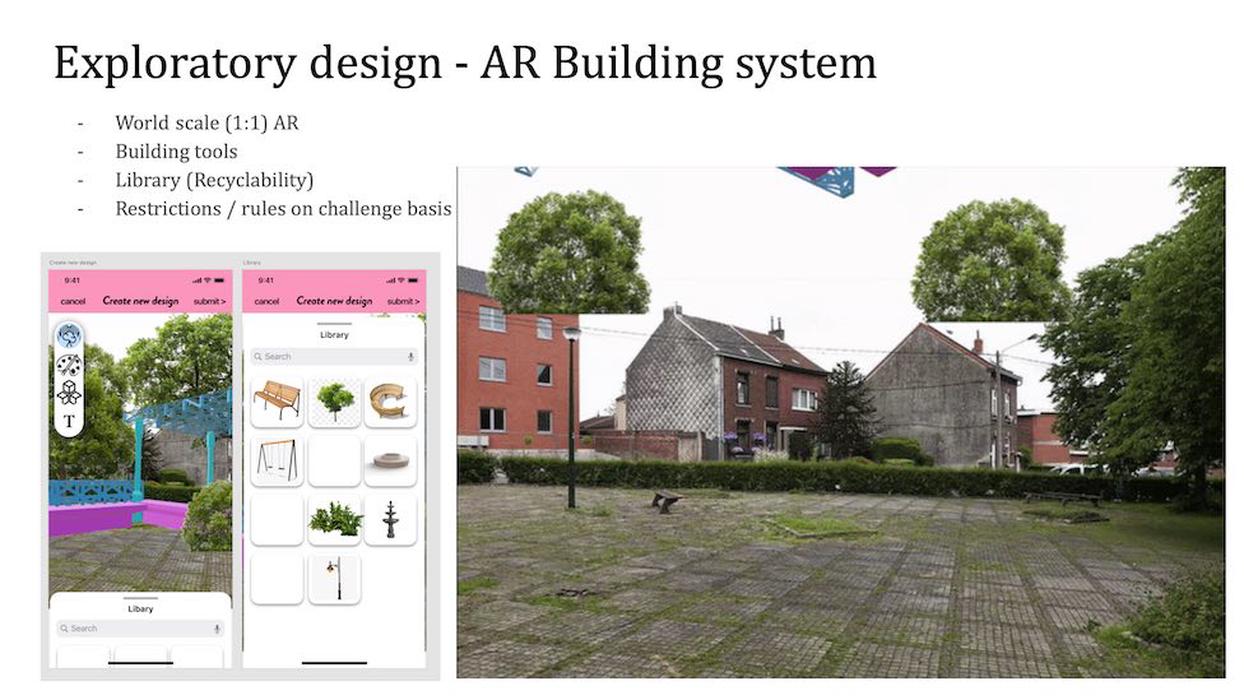

The novelty in our idea of collecting citizen input was to utilise world-scale Augmented Reality. This allows citizens to indicate what they want in their neighbourhood to change directly in the context of the real world. Municipalities could then see where something needed to be changed. Next to municipalities, people could see what other people wanted changed and this could spark discussions.

Drawing of how people's ideas would be placed and retrieved in the world (23 September 2020)

Drawing of how people could add things to the world and gamification (23 September 2020)

Brainstorming session (24 September 2020)

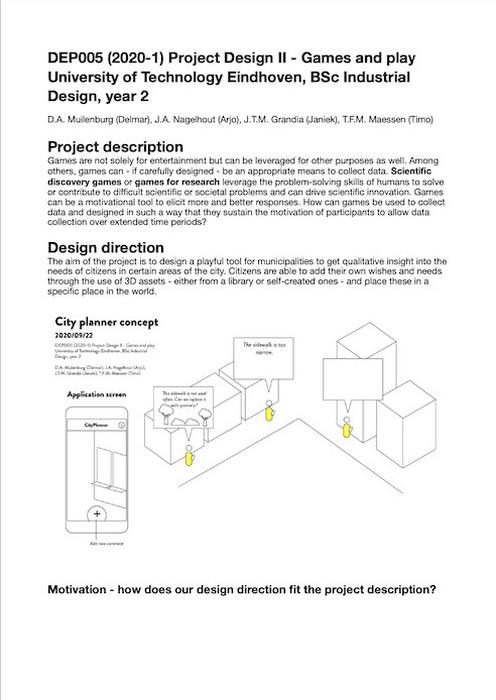

Cityplanner concept

Concept definition

We created a design direction document, which specified what direction we wanted to go in moving forward:

Design direction document (23 October 2020)

Because of the large difference between the previous presentation for the pressure cooker and this new concept, we put a lot of work in the presentation. We defined our new research question, as well as linking it to current research.

Our research question was now:

“How can we improve engagement of citizens in urban planning and public space design efforts of municipalities using gamification and emerging technologies as location based augmented reality?”

Next to that we defined our target group (Presentation slide 3).

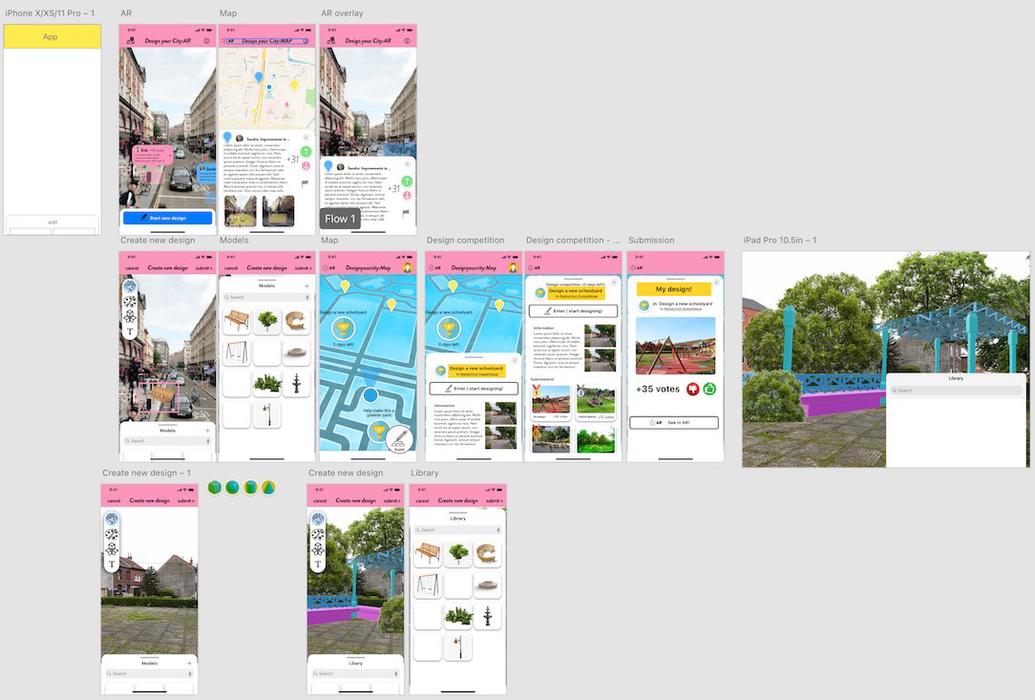

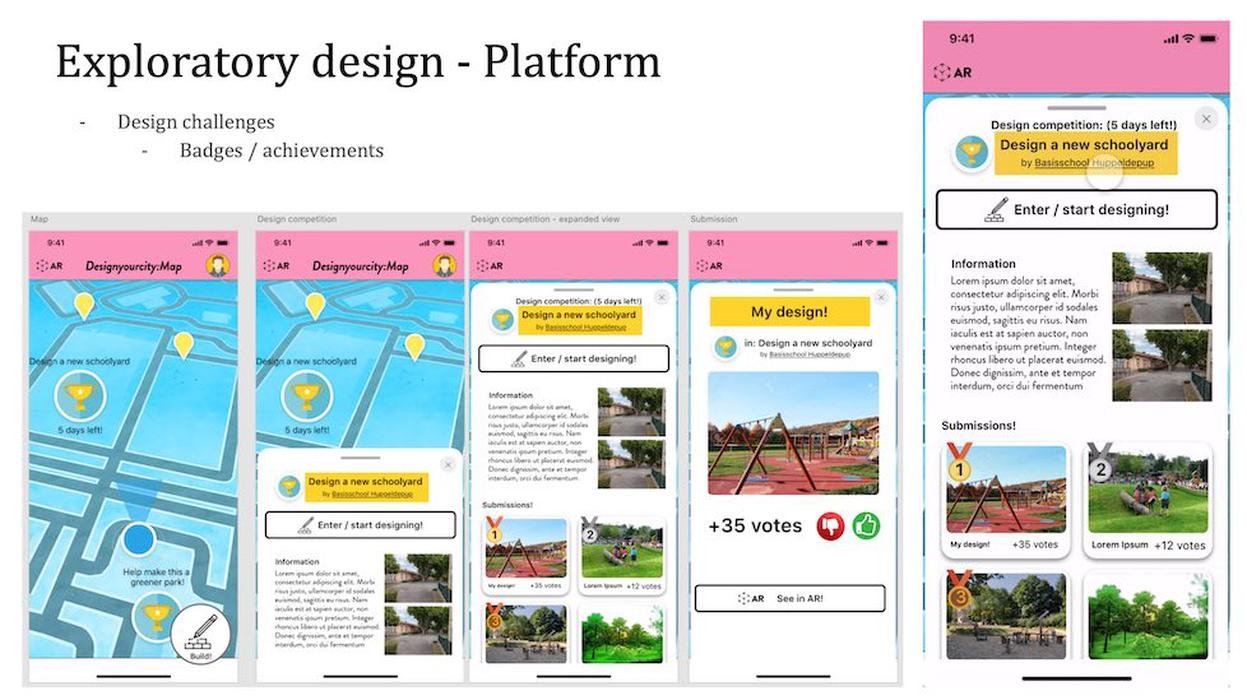

To illustrate our idea we created multiple visualisations using Adobe XD and Blender, which can be seen both in the presentation (Slide 5 and Slide 6) and in the following videos:

Adobe XD mockup of application (25 September 2020)

We also started looking into whether there were research papers published in the field of citizen participation in urban planning, and we came across the paper “Citizen Design Science: A strategy for crowd-creative urban design cities.”. The researchers of this paper created an entire web application for getting people to give input on certain problems in urban design in a given city. This application also introduces a social aspect, where people can vote on the ideas and participate in meaningful discussions. The fact that this paper existed confirmed that we were going in the right direction. The application itself however was not fun or engaging to use and we saw the opportunity to improve this experience greatly by using an augmented reality interface.

Presentation

Presentation slide 1 - A playful tool for increasing citizen participation in urban planning

Presentation slide 2 - Overview

Presentation slide 3 - Research question and target group

Presentation slide 4 - Societal relevance

Presentation slide 5 - Exploratory design - Platform

Presentation slide 6 - Exploratory design - AR Building system

Presentation slide 7 - Process

Presentation slide 8 - Moving forward

References

- Cooper, S. The challenge of designing scientific discovery games. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. June 2010. Pages 40-47. http://doi.org/10.1145/1822348.1822354

- Mueller, J. Citizen Design Science: A strategy for crowd-creative urban design. Cities, Volume 72, Part A. February 2018. Pages 181-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.018